The poetry collection that most impressed us in 2018 was Floss by Sarah Crewe (Aquifer). Crewe compounds feminism with a psychogeography of Liverpool. At HFP we sometimes describe psychogeography as “going somewhere to see what isn’t there”. By adding female and working class history, Crewe raises the question of why particular things are not there, even in the historical record that W.G Sebald and his fellow travellers rely on. Things unrecorded or suppressed.

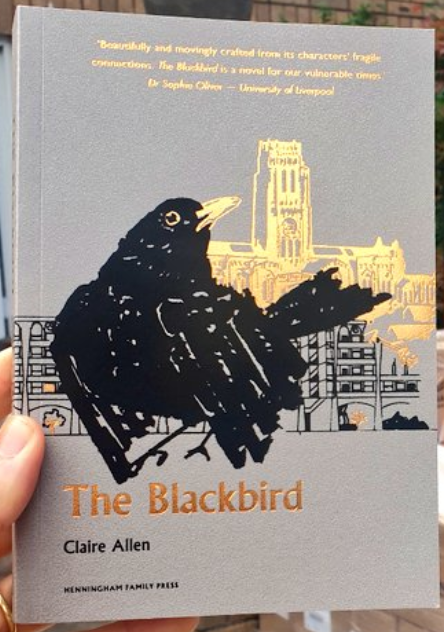

Floss is set on the page to mandate a rhythm and contemplation of each phrase that, while not the first poems to do so, still manage by dint of skill and verve to become revolutionary. Something Crewe performs in person extremely well. We were delighted she agreed to talk with Claire Allen about The Blackbird:

Sarah Crewe: There’s loads I wanted to talk about with The Blackbird as I enjoyed it so much. But thought I’d start with this: I’m currently obsessed with the Sisters of Mercy song, Heartland, as it speaks to the psychogeographical backdrop to my own poetics, which is largely the cities of Liverpool and London. The Blackbird did the same for me in cutting across these two locations. In the case of Liverpool, you’ve gone very specifically for the scope of L3, stretching from Hunter Street on the outskirts of Vauxhall, across to Hope Street, where the cathedrals are located. With the London location for Louise decades later, my imagination leapt from the social housing that was based around The Cut to the old Heygate Estate at Elephant & Castle. I was wondering what made you decide to place the characters in the times and locations that you did. Was it the cathedral that drew you in? Or did you want to cover Liverpool in the Blitz as a lesser known epoch of WWII history?

I should declare my interest in L3 here also. I’m originally from that area and the paternal side of my family are all from that area, right up to my great great grandparents living in Vauxhall. Two of my great grandmothers and great grandfathers grew up in the former slum housing off and around Hunter Street, my paternal grandmother was from Hunter Grove no less. So Blackbird starts on the site of the ancestors, which was a major hook for me personally.

Claire Allen: It’s really interesting that you were imagining the social housing around The Cut as well as the Heygate, which is actually what I based the Blackbird Estate on. I used to go past the Heygate on the bus every morning during the long process of demolition, and, even though I’d never been inside, I grew quite attached to it and was sad when it was eventually reduced to nothing but a pile of rubble. I can’t imagine what it must have felt like for the people who’d lived there.

It’s also really interesting that you have a connection to the blocks around Hunter Street. I based Albion Gardens, where Thomas lives, on the Gerard Gardens block which I think was fairly close by! I noticed the references to St Andrews Gardens in your book, so I was wondering whether you had a particular connection to those flats.

SC: Ah, Gerard Gardens! I always regarded that as the twin set to the Bullring, and have always been curious about the parallel lives and stories that must have occurred between the two locations.

I’m delighted to have been so on the money with the Blackbird Estate location! Somehow the SE1 structures just fitted what I was conjuring up as a reader.

The disappearance of the Heygate was just so weird wasn’t it. And yet simultaneously, it seemed to take forever to dismantle it. Almost like it just wouldn’t come down. I don’t blame it. I think what you’ve touched on in terms of how you felt about it finally vanishing is loss. I really felt that at the end of Blackbird when the estate is described as rubble, it’s a really emotional ending. It made me think sadly of all the former tenement blocks and the real lives and families that have taken place and refuge* in them. And I think what the text also touches upon is the pride that people in those communities took in their own homes for all those decades. I was a teenager when the blocks my family grew up in were ripped down, and I don’t think any of us really externalised it as a grieving process until much later.

* I’ve asterisked this as I think it’s an important word in the context of Louise. It’s clear that, in spite of living in the type of housing that various sections of society would turn their nose up at, she feels safe. I thought the fact that Benny (who poses a palpable threat to her safety) is positioned as a boy who is from both a different area and a privileged background, was really powerful. It serves as a potent reminder that violence, in all its forms, is not restricted to working class males. Which is quite contrary to the narrative served up frequently by various hierarchies. I also thought the way in which Jenner tries to exert control over Hope’s mother, Mary, amplifies the same point. Was this a deliberate strategy to invite the reader to think about the ways in which gender based violence is not as simplistic as it’s often portrayed, on both class and methodical levels?

CA: That point you raise about male violence and privilege is a really important one. I very much wanted to get the reader thinking exactly as you suggest, because male violence is so often seen as a primarily working class problem and it absolutely isn’t. So it was a very deliberate choice to have Benny come from a more privileged background than Louise. Male violence and controlling behaviour seem to be a bit of a recurring theme for me, and I think it’s so important that it be recognised as something that is absolutely not absent where there is privilege.

What you say about loss, in terms of the Heygate’s demolition had me thinking ‘Yes, yes, yes!’ That is exactly it, and when I was researching how the end of the Heygate unfolded, it became clearer and clearer just how attached to their homes the tenants were. The blocks had been built as large, light, big-windowed flats and, grotty as they seemed, they were good homes to the families who lived there, and for the most part people were sad and reluctant to leave. And then, when I looked into Gerard Gardens, I found the same thing – a community of tenants who were proud of where they lived and didn’t want the flats to come down at all. And, with both places, there was that seemingly deliberate decision to allow the place to become run down, to allow negative associations to accrue around the idea of the place, so that the narrative that ends with demolition started to seem inevitable. It’s really nasty. And both places lasted only about 40 years. I really love parallels, so I was really glad to have that echo between the two estates.

You asked about time period and location, and wondered why I’d chosen Liverpool in 1941 and London in 2014, and not the other way around. I think it was to do with the cathedral – because for a while I’d had an idea that I wanted to write a novel about the building of the cathedral, and gradually that sharpened into something that focused on the building of the tower and the fact that it happened at a time when the city was being bombed. I liked the opposites of a tower going up when everything around it was coming down. And the ever-present threat that the tower itself could come down, which led me to William Golding’s The Spire, which has the same looming possibility hanging over the whole novel.

Thinking about your book now, one of the poems that has really stuck with me is emporium, which conjured, for me, the fabric shops that there used to be round the back of T J Hughes. I can really remember going there as a child with my mum. That poem really seemed to encapsulate one aspect of your writing, in the sense that it gives a vivid and immediate sense of place, whilst also being a kind of explosion or simultaneity of images and impressions. I wondered how you had arrived at that particular style – whether the fragmentation of form and images in many of your poems came about because it felt closest to the truth of things.

SC: Thanks so much for your kind words on emporium from floss, I’m really happy to hear you enjoyed that poem so much! You’ve located this poem to a tee, Stafford Street, the fabric shops! Fabrics and colours are at the bare bones of my poetics, I’m seemingly obsessed with them. My Mum had red velvet curtains in our flat on Gill Street during the 80s, and when she was done with them, gave them to me to use for making Barbie clothes. I’m really pleased that you were able to locate just how important the aspect of fabric, materials and working with what’s available on a sensory level is to my work. But it really does stem from that, which to me is my girlhood. The excitement I found in colours and textures has been transferred to words and subsequent poems. It’s a massive case of unravelling and still learning. Trying to expand on a piss poor vocabulary (!) by using a range of different sources: walking notes, photographs, archives, books, films, paintings. And in terms of stylistics, using words as fragments and threads seems to suit the themes of what I write about much better. A lot of people don’t think in linear statements, there’s a myriad of ways in which impressions are made. Fragments and a mosaic approach are often much closer to the truth of a thing than a full sentence, so poetry works as a perfect medium of expression for this. There’s a brilliant Audre Lorde quote:

There is no such thing as a single issue struggle because we do not lead single issue lives.

I feel this strongly applies to poetics. It doesn’t need to take one straight path or one sole master narrative, because that’s not a truthful reflection on our lives or our thoughts, our imaginations. So many aspects, so many stories, are intertwined, which is what I’m hoping to convey through a poetics of working class feminist psychogeography. And I feel the entire concept of interwoven women’s stories is one that runs straight through Blackbird, which is one of the reasons why I enjoyed it so much!

There’s a line about halfway through the book:

invisible wires, each exerting a pull until they are brought within range of each other

This really spoke to me in terms of how people are drawn together through shared experiences, and I felt it was especially relevant to working class lives. What you’ve saying about the Heygate really confirms that, and I love the way those details have imprinted themselves so hard into your memory. The large, light, big windowed flats. That’s exactly what the windows were like for Gerard Gardens and St. Andrews Gardens too. I was only reading a piece just yesterday on how the Government have just extended Permitted Development Rights. Meaning they can bypass minimum space standards for housing and windows within new build apartments. Not only does this sound like a disaster waiting to happen, but also such a far cry from both the aforementioned housing schemes. The windows were such a centre of pride, and some flats (say about two or three per landing) were even lucky enough to have verandas. They were very well kept. It was only when the flats began to be boarded up, and demolition plans became visible, that they started to look dilapidated.

Back to the text, I love the way you’ve named Albion Gardens as such, as in its poetic sense, like William Blake’s New Jerusalem. Even though you can detect Mary’s reticence when she goes to visit Thomas, the reader knows full well that there’s something of “the stranger in the field” to her impression as opposed to what the truth might be. You’re absolutely right about the deliberate nature of the “dangerous place” narrative that was allowed to fester about Gerard Gardens. It was the absolute manifestation of the Thatcherite managed decline policy of the 1980s. But this continued with the Heygate. Back on the parallels, have you ever watched Violent Playground, that was filmed around Gerard? I haven’t, but can’t help but consider how the Heygate has also been used for films and music videos (including Madonna’s Hung Up ) also. It feels so bitterly sad that two sites that were appropriated for film weren’t deemed worthy of saving for people’s actual lives.

I did feel the choice of demographic for Benny had to be a conscious decision, and think it’s a really striking aspect of the narrative. What I enjoyed about that juxtaposition is the contrast of Carl. Because in him, the boy she grew up with on the estate, we see a decent man, with strong values, who clearly loves Louise. There was, unfortunately, a narrative of “for God’s sake, don’t marry anyone from round here!” from parents who wanted better for their kids from these estates. Yet in Carl, the twist is provided of “actually, Carl from the estate isn’t a threat. University educated, Mummy’s boy Benny, he’s the one who needs to stay away from you.” The scene where Louise recalls mentioning Jake to Benny’s mother on the phone, and she goes silent, is brilliant by the way. Obviously, Benny has failed to mention Jake’s existence. It feels like the usual positioning of nice middle class boy who provides for his family vs lad from council housing who gets girl pregnant and runs away has been utterly turned on its head. There’s other such details that provide tiny glimpses into Benny’s character too – like when Louise remembers him claiming to have skinned a rabbit once, and it’s just left in the air hanging for the reader to construct their own possibility from. For me, it was all the more terrifying – it takes a certain amount of detachment to be able to skin an animal, not least a rabbit. But then I also recognise that’s an urban privilege talking. I’ve never had to. But then there’s no way Benny had to either. It’s like information he’s dropped into the conversation to let Louise know that he’s capable of some form of violence. I think these methods you’ve used to provide small insights into his level of thinking are way more effective than straight up presentation of “here’s a thug.” And yet, he so clearly is. Even when Louise laughs off his statement along the lines of “if you want things to go well for you, you’ll do as I say”. As a reader, I was scared for her at that point. But she continues to be steadfast and stoic. Again, I think that’s so compelling. The victim mentality trope of girl afraid (not least, in film that is presented as horror) is so overused when presented with violence in text or on screen. But the reality is that violence can happen to anyone at all. No amount of courage can prevent it. While that is such a depressing prospect, it’s important to recognise and acknowledge, and I think Louise’s story highlights both the falsehood of fixed narrative, and the intricacy of survivors’ lives.

I haven’t read the William Golding book, but would like to now! I know the cathedrals are a powerful pull for writing material though so I totally get why you’ve positioned the time frames and locations for Blackbird in that way. Historically it’s also interesting, as I genuinely didn’t know about the “bouncing bomb” and the Anglican until reading Blackbird and looking it up! The book really highlighted for me that I’m still learning about Liverpool during this period, and I suspect it’s the same for many people. When describing the bombings, you mention a church, St.Michaels, on Upper Pitt Street. I had no idea that church had even existed. This crosses over a lot with my own work at the minute, as I’ve just referenced St.Mary Highfield in a poem, another Liverpool church that was lost in the Blitz. I did enjoy the level of detail you’ve gone for in this particular part of the book as well, you reference the SS Malakand, which again, I’ve also mentioned in a poem about the actress Mary Lawson, who also died during the Liverpool Blitz (and as I type this I’m wondering if she was behind your choice of name for Hope’s mother?)

CA: Mary Lawson – no, I don’t know about her, so you’ve given me someone to do a bit of research about! I love this more than anything about writing – the fact that you end up finding out about all kinds of people and stuff you never knew you needed to know!

Yes, I read something recently about those changes to permitted development and how manky old office buildings can now be converted into homes, and there was an example of a building that was essentially in an industrial estate, with no infrastructure anywhere nearby, no shops, doctors’ surgeries, nothing. And there were diagrams of the proposed flats and they were tiny, with no windows. Utterly criminal. As you say, a disaster waiting to happen – and you’d think the government would learn about housing and disasters given recent history – and so very far away from the ideals that went into town planning in the not-very-distant past.

I feel I’m becoming more and more interested in housing. The book I’m in the middle of writing is very much concerned with poor housing and the gated developments which are the other side of the coin.

I have seen Violent Playground. That point you make about how places can be appropriated for film, but not deemed worthy of maintaining for people’s actual lives is spot on. Completely upside-down priorities! And of course the films themselves help feed the ‘dangerous’ narrative… There was a documentary called Gardens of Stone which I found out about but never actually saw – made by former residents of Gerard Gardens, which looked really interesting – giving a sense of the community that was lost when the flats came down.

I’m really interested by what you say about Benny and the rabbit skinning. I’d originally had in my mind that he was a bit of a fantasist, and didn’t necessarily always tell the truth. And so the danger Louise is in isn’t as apparent to her as it might otherwise have been because Benny is someone who talks the talk but doesn’t always fit the action to the words. But I like the added sense that skinning a rabbit could very well be something he has done, and it’s his detachment and streak of violence that has enabled him to do it. I’m glad that you got a real sense of Louise being in danger at that point where he says ‘If you want things to turn out OK, do as I say’, because I really wanted the danger of that kind of controlled manipulation to come across. Coercive control might now be recognised as a form of domestic violence, but control can be so gradual, so subtle, so clever, that I guess it’s not necessarily easy to know when it’s happening.

I’ve been rereading floss and it’s interesting reading it in the light of what you said about the excitement of colours and textures being transferred to words. I keep getting a real sense of your playfulness with language – with the sounds of words and how the sounds of one word link to another word ‘&so on / & sewn on’ cropped up in what I was reading last night – but so did so many other word and sound references and, kind of, ‘riffs’ ( I hate using that word – it’s such a jazz buff sort of word – but it sort of fits with what I’m saying!) What you say about your approach to poetry – the fragments and threads – the combination of walking notes with images, research etc – really made sense in terms of truthfulness to how lived experience is. As you say, we don’t think or experience things linearly or narratively and so poetry, being more kindly disposed to ‘snapshot’ representation from all kinds of sensory directions all at once, can be truer than the sometimes plonkiness of novels. I really like how you’re weaving together women (and women across time in the three poems about Ann Fowler’s), locations, loss, absence, language. It’s great that you feel The Blackbird links into similar themes in terms of interlinked women’s lives. What I found really fascinating in my own writing was the echoes and parallels that emerged as I went along. I wonder whether you also found echoes starting to resound, once you’d started…

SC: I’m really taken with the theme of echoes, capillary waves and reverb (My turn for the muso terminology there!) throughout both our writing projects. As a reader I loved the realisation that Robert had designed the children’s statues for the estate that Louise and Carl had grown up on. It was so subtle, and completely believable. It also spoke to me on how lives can intersect on a cross-class level. I think the arts have great potential in this area particularly, and to see jobs and funding being currently decimated as they are puts the chance and opportunity for people to learn, consider and cross pollinate into each other’s lives less and less. It’s the same with housing. The industrial estate model that you describe in London is quite frightening. It reads like the only lesson the Government is taking away from previous housing disasters is “don’t get caught”. What concerns me even more is that, post Grenfell, there seems to be an attitude of “if we use the right cladding, then what can they possibly complain about? As long as there’s no tragedy, then we’re good to go.” When actually the issues around quality of life in housing structures run so much deeper than no fire hazard and ticking all the H&S boxes.

I’m actually delighted that you used the term “riff” for floss (minus the jazz, which I have a comical aversion to). Musicality is very important to me and I also like the idea of words dancing round the page and coming off it into the reader’s head. I’m into assonance and resonance, not just in language but also between people’s lives, across time frames, scales and threads. When I was researching the ancestors for floss, I couldn’t quite believe the parallels between both sets of paternal great grandparents, to the point whereby I refuse to believe they hadn’t met beforehand. I think what also interests me is aftershocks. Like, is the Cathedral in Blackbird the main explosion, and all the subsequent lives that come from it the later tremors? Or is it the broader global event of WWII? What struck me when writing floss was how the lives of the 21st century are still so impacted by those of the 19th. I’m really happy that you liked the reverb of the Ann Fowler poems. Again, the stigma and sociological backdrop to women seeking refuge from domestic violence really echoed through into more modern times. I’m also wondering on this point how we go about breaking destructive echoes, and how to move forward from them? It seems for Hope, towards the end of the novel especially, knowledge of how her mother dies isn’t power. Instead, the affirmation is in her right to decline, to say, “enough, the past stops here.” And I love the way her relationship with Robert unfolds as a whole new life. Which, in spite of his downturn in health, has been a happy one, a real love story.

For me, psychogeography works as the imprint geography leaves on the psyche. It’s a very active, fluid form of poetics that combines the historical, the socio-economic and the personal, as no two people will have the exact same response to geographical surroundings on a dérive. There’s a book edited by Dr.Tina Richardson, Walking Inside Out, which is an excellent and varied collection of essays on how psychogeography means many different things to various demographics, I think you’d really enjoy it. When I was reading Blackbird I was thinking how much fun it would be to do a walk based on the Liverpool setting, starting from Hunter Street and moving across through the Georgian Quarter, but via Erskine Street in tribute to Louise, obviously! Did you go on any such walk when you were gathering notes for the book, or is it all from memory and/or footage?

That’s such a pertinent point about Louise perhaps not realising the danger she’s in, in spite of various flags being raised for the reader. Foolishly, it hadn’t occurred to me that Benny could be full of shit about the rabbit, but it’s obviously a factor for her. It’s a set up with so many layers to it. To people on the outside of any coercive control situation, it’s so seemingly easy to see the flags and be screaming START THE CAR, but to the person on the end of the harm, nothing is that clear cut in any way at all. Again, it’s an example of perceptions of survivors vs the reality, which is complex and variable. Louise’s story really does demonstrate that nothing in an abusive relationship fits the exact same narrative as another.

I’m actually really pleased to hear that your next writing project is about housing, as from both Blackbird and these conversations I can see this is something you’re both knowledgeable and passionate about.

CA: Yes, resonance, that’s a good word, and at the root of a lot of what we’ve been talking about – the echoes and parallels, and, as you say, the reverberations that sound for so long afterwards. I like your idea of one thing being an explosion with a series of aftershocks, and the need to break free from destructive echoes. But I’m also thinking of one of the poems at the end of floss – anfield fleet maintenance – and the need for the invisible, the many who have slipped through the net in whatever way – through being women, through being poor, etc, to have a history. So I guess it’s a balancing act: on the one hand maintaining links with the past but on the other breaking the harmful repeating patterns. That poem, as well as explaining the two personas of floss and flick, is very clear about the kind of palimpsest (oh, I love that word!) nature of places, how cities, in particular, are made of layer upon layer of history and the pavements have layer upon layer of stories to tell, the streets teeming with their own past lives.

I’m glad you see that break with the destructive echoes coming through in Hope’s decision not to find out what happened to her mother. As you say, it’s an affirmative decision she makes to lay it all to rest. And then, at the end of the novel, she kind of makes her peace with that earlier decision, as she realises that, sometimes, letting things stay lost (like the sculptures in the pub garden) is the best option.

I love the idea of a ‘Blackbird walk’ round Liverpool! I didn’t do that as part of the planning process, though it would’ve helped me get my bearings a bit! I find that I’m really hazy these days about what is where in Liverpool! I relied on memory for the area around the cathedral, and finally managed to make a trip up the tower after the book was finished, and then afterwards had to rewrite a few bits, when I realised I’d got stuff wrong. Like the fact that you can’t actually see the Runcorn Bridge from the top, as I’d thought! But for Gerard Gardens I relied on photos, mainly.

SC: Haha, I was actually wondering which one of us would be first to use the word palimpsest. It’s a word I love too! I think that’s such a crucial point you make about maintaining equilibrium between the past and the present, and trying to see what kind of future we can carve from both. I read Lola Olufemi’s Feminism, Interrupted earlier in the year, and she makes such a potent case for feminism being a forward looking, progressive politic in which we need to imagine a more positive, better world for everyone. But I feel that in order to understand what is needed for the future, we need to be cognisant of both the past and the present, and what it entailed for those who went before us. In that poem, anfield fleet maintenance, the spotlight is especially on Anfield, because as an area, its Victorian past is essentially staring us in the face at the end of every street. An area that relied so heavily on 19th century benefactors, continues to require food banks and charitable intervention in the 21st. That galls me. The lesson is that it is going to take more than the benevolent intervention of the rich to truly make a change to the harmful cycles of poverty and hardship that continue to exist throughout the history of specific postcodes.

CA: Well I’m glad we managed to shoehorn ‘palimpsest’ into our conversation! I’ve really enjoyed unpicking and talking through all the threads that run through both our projects, particularly those resonances between past and present. What you say about the need to understand the history of the places we live in and the people who came before us is so true. It has a particularly sharp resonance now, I think, in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement and the cultural reassessment that is starting to take place as we look collectively at the history of the sites, institutions and monuments that surround us and that we are part of.